It started with pictures of a Syrian-Kurdish boy washed up on a Turkish beach. Images of three-year-old Aylan Kurdi lying lifeless on the sand provoked an outpouring of compassion around the globe.

Since then, the Syrian refugee debate has raged and the number of migrants has swelled. Who is to blame? How many will we take? Should others be doing more?

These are now common questions across Europe as the continent faces its worst refugee crisis since the Second World War.

For the boy’s father, Abdullah, the solution rests closer to home. “I want Arab governments – not European countries – to see (what happened to) my children and because of them to help people,” he told reporters.

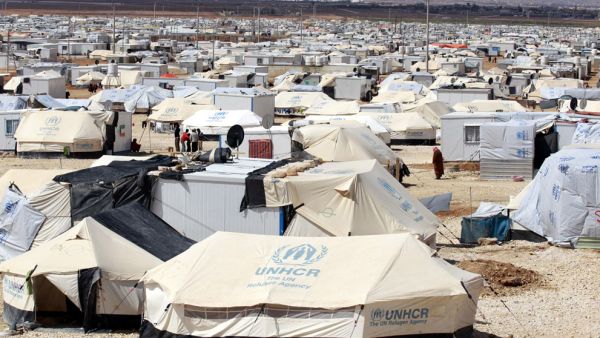

To date Lebanon, Turkey and Jordan have absorbed the majority of the conflict’s four million refugees. However, many voices have criticised members of the Gulf Cooperation Council for not doing more.

In terms of financial support at least, regional governments are among the leaders. Kuwait is the fourth largest donor with $325m of aid committed. This compares to $1.1bn from the United States, $454m from the United Kingdom and $406m from the European Commission. Saudi Arabia ranked sixth on the list with $214m committed and the United Arab Emirates 12th with $86m.

The money has attracted little applause from humanitarian groups. Especially, given the alleged funding of Islamist rebels in Syria by GCC governments and participation in a separate conflict in Yemen.

“To me, buying your way out of this is not satisfactory,” said United Nations special representative Peter Sutherland. “And I say that taking refugees is separate from giving money.”

Last year, Amnesty International said Gulf states had offered “zero resettlement places to Syrian refugees”.

For their part, Gulf nations have responded with their own figures detailing the number of Syrian arrivals. The UAE said it had provided residency permits to more than 100,000 Syrians since the start of the conflict in 2011, with 242,000 Syrian nationals living in the country.

Saudi Arabia, meanwhile, said it had taken in 2.5 million Syrians since the conflict began. Kuwait also announced last month it would provide long-term residency permits to Syrians who had overstayed their visit visas or could not produce the appropriate documents.

But there is no distinction between migrant workers and refugees here. Even in times of peace, large numbers of Syrians have travelled to the region for job opportunities.

Countries like Qatar and the UAE have built their economies on large-scale transient foreign labour. Up to 85 per cent of each country’s population is made up of expatriates only granted residency with secure employment. A sudden influx of refugees would upset this status quo and have implications for security, it is argued. There is no guarantee that those fleeing the conflict would want to return home.

Then there is, of course, the drain on public resources and subsidies at a time when government coffers are stretched by low oil prices.

But these are concerns shared with Europe. A region that has far less in common with Syria – in geographical, cultural and religious terms – than the GCC. It is also difficult to see how controlled migration would be completely unmanageable. There are many established Syrian communities already across the region that would provide support.

The UAE’s population stands at around 9.3 million. Should the country take on a few thousand refugees, this is unlikely to upset the balance significantly. Neighbouring Saudi Arabia, with a population of 28.8 million, would feel even less of an impact.

“Instead of talking about funding mosques, Saudi Arabia should be thinking about taking refugees,” said Germany’s Christian Democratic Union deputy chairman Armin Laschet following an offer from the kingdom to fund the building of 200 mosques for refugees.

As Gulf nations continue to assert themselves in regional conflicts, they may well be expected to open their doors as well as their wallets.

By Robert Anderson