For his Beirut solo, “Sand Comes Through the Window,” Taysir Batniji had to redo pieces from one of his major series from scratch.

“When I did the work in 2012, it was different,” the Gaza-born artist tells. To make “To My Brother,” he took old pictures of his brother’s wedding and engraved the images into paper, tracing inkless outlines of the bride and groom, kids popping up in the corners of the frames, details of the wedding dress and lights in the background.

Almost completely indiscernible if viewed from a distance, up close the images are like soft, monochrome illustrations ripped from a precious book.

The original photos were taken in Gaza in 1985. Just two years later, on the ninth day of the first intifada, an Israeli sniper killed Mayssara Batniji.

A haunting sense of presence-absence permeates “To My Brother.”

Batniji says that creating the work, over two decades after Mayssara’s death, not only brought back memories of his brother but of other family members and his life back then.

“Not being able to go to Palestine,” the France-based artist says, “you feel like this period of your life belongs to another time or another person.”

He says he spent about two months creating the pieces. “It’s very time consuming,” he adds. “For many of them, one drawing was like one day. During the two months, I really felt like I had him [Mayssara] present with me.”

Batniji’s series was among the winners of the 2012 Abraaj Group Art Prize. After exhibition during Art Dubai, the emirate’s yearly art fair, AGAP-commissioned works became the property of Abraaj Capital, the former private equity fund, which promised to make these pieces available to exhibitors. Artists were allowed to produce copies of their commissioned works, an option Batniji didn’t pursue.

“Many people asked me, ‘Why you don’t make another version?’” he recalls, but “it is for me hard to repeat this experience again and to live these feelings again ... and I always refused.”

He says he also didn’t want to sell or make commercial editions of the works, so he thought one copy would be enough.

Abraaj collapsed last year, and Batniji says he’s been unable to access the series since. He decided to remake a selection of six of the original 60 works this year for the Beirut show. This time, he says, it felt “like going to a place that you have seen before, or you lived in or you spent time in, and finding it empty.” He had to look for another way to reconnect.

{"preview_thumbnail":"https://cdn.flowplayer.com/6684a05f-6468-4ecd-87d5-a748773282a3/i/v-i-c…","video_id":"c9cfb308-e7b0-4a7c-8ad3-a61a488e271a","player_id":"8ca46225-42a2-4245-9c20-7850ae937431","provider":"flowplayer","video":"Have The US Sanctions on Iran Been a Success?"}

Presence and absence and things not being as they might immediately appear are strong motifs in Batniji’s practice, along with links to family and a sense of being in-between.

His poignant works explore ideas that are often highly personal yet universal - specific to the Palestinian diaspora yet somehow accessible to anyone who is far from their family or homeland, or who has experienced loss or displacement.

In “Disruptions,” 2015-2017, the artist has taken screenshots of WhatsApp video calls with his relatives in Gaza. Bright green, angular blocks of color and patches of image with little or no detail capture the look of an interrupted connection.

Though the work stems from a literal representation, Batniji notes that some of his other works explore this difficulty connecting in a more meditative or conceptual manner. He stopped work on the “Disruptions” series when his mother passed away.

Perhaps the most formally striking work in the Mina Image Centre show is “Watchtowers,” 2008.

Shown here in its entirety, the series takes Bernd and Hilla Bechers’ cornerstone-of-photography work on “typologies” of industrial architecture and subverts it.

Viewers soon realize they aren’t looking at photos of water towers, but Israeli watchtowers.

Unable to travel to Palestine, Batniji commissioned a young artist in the occupied West Bank to take the photos for him, a task both formally challenging and physically dangerous.

Batniji’s works illustrate how far contemporary photographers have pushed the form’s boundaries since the classical approach of Irving Penn, whose images were featured for the MIC’s inaugural exhibition earlier this year.

Phone screenshots of videos, images that challenge the idea of photographer/artist (Is it the person who pressed the shutter?) and work that draws on the Bechers’ influential series are a long way from Penn’s classic portraits.

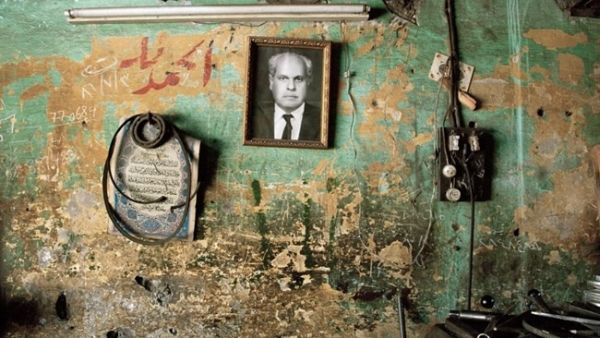

“The photo for Taysir is not just an image that you take with a camera,” MIC Director and exhibition curator Manal Khader remarks to The Daily Star, “it’s also something that you do with your hands - the tracing of the photographs of his brother, the traces that a photograph can leave on a wall in the painting.”

Batniji “can represent the other end of the spectrum of what photography is, and [holding this exhibition] is in a way to say ... ‘Look where we are, where we were’ - and eventually I would like to be introducing what is in between.”

The exhibition’s title takes inspiration from “Snow Comes Through the Window,” a novel by the late Syrian author Hanna Mina that Batniji read in the ’80s. “The connection came in 2003 while crossing the border with Egypt, with all the difficulties I had,” he says, adding that he wrote a text about the journey that he titled “Sand Comes Through the Window.”

“Crossing the desert, you are crossing a sea of sand. Sometimes you see nothing - maybe some palm trees here or there. Suddenly, somewhere through the journey you see a man walking. You don’t know where he’s come from and where he’s going. ... Sometimes you feel like maybe, because you were tired, because it’s really a very tiring journey, you think, ‘Maybe this is just my mind, a kind of illusion.’”

Sand is also an element that has come up in some of Batniji’s other installations and performances.

“Each work I start looks like a kind of specific and unique experience,” he reflects, “but when I look afterward, I always find connections between works, in one way or another.”

“Sand Comes Through the Window” is up at the Mina Image Centre until Aug. 11. For more, visit minaimagecentre.org.

This article has been adapted from its original source.