A complex of narratives have been erected around the Palestinian refugee camps in Lebanon. Certain non-Palestinian circles favor tales depicting the camps as “security islands,” spaces where, in lieu of Lebanon’s exacting system of law enforcement, lawlessness rules.

There are also more nuanced representations of the camps. These tend to detail how refugees’ quality of life, which declined precipitously after the exit of the PLO in 1982, has been further proscribed by UNRWA budget cuts and legislation outlawing most Palestinian participation in the Lebanese workforce.

A pall of gloom unifies these “pro” and “anti” refugee narratives. At times a skilled filmmaker will make aesthetic virtue of grim necessity – witness Maher Abi Samra’s 2004 documentary “Shatila Roundabout,” a sensual amble through Beirut’s best-known refugee camp. It’s difficult for filmmakers to overcome the pall completely, though, because the material circumstances of Palestinian refugees in Lebanon are irrefutably grim.

Mahdi Fleifel’s “A World Not Ours” is a documentary about Ain al-Hilweh camp. Located on the fringes of Saida, it has the distinction of being the largest of Lebanon’s refugee camps, one with a reputation for raucous militancy.

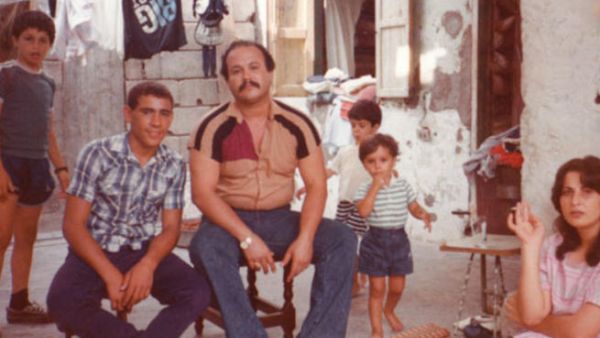

Fleifel makes no reference to past journalistic depictions of Ain al-Hilweh. Rather, he sidles into a stylishly intimate documentary that is as much a filmmaker’s coming-of-age story as it is a history of the camp refracted through the experiences of family and friends.

The film’s personal narrative approach has attracted some attention since premiering at TIFF. Last week “A World Not Ours” walked away from the Abu Dhabi Film Festival with the Black Pearl for Best Documentary as well as the FIPRESCI (international film critics guild) award for documentary and the NETPAC (Network for the Promotion of Asian Cinema) prize.

“I’ve always wanted to tell the story of Ain al-Hilweh,” Fleifel says to the accompaniment of a cool jazz soundtrack. “For years I thought it meant ‘Beautiful Well.’ Actually it translates as ‘Sweet Spring.’”

Both translations are ironic, he notes, since camp residents struggle to find anything sweet or beautiful here.

By degrees Fleifel reveals that his 80-something grandfather first arrived at the camp when he was 16-years-old. Since then he’s never left the camp, refusing to join his daughter in Denmark because he doesn’t want to risk losing his right of return.

Though born in Ain al-Hilweh, Fleifel spent his early years in Dubai and he and his family later migrated permanently to Denmark. When he was seven Fleifel’s family returned to the camp, and it is here that he really grew up – spending much of his time at the local cinema, watching U.S. action films.

The charm of “A World Not Ours” is that it makes the details of the family’s migrations and the camp’s political history equally secondary. The story is buoyed-up by the filmmaker’s recollections of spectacle – especially the every-four-years pageant of the FIFA World Cup – and the desire to capture images on film.

Recollecting the spring of 1985, to the ubiquitous jazz accompaniment, Fleifel recalls that “Life was all cartoons and Michael Jackson videos.”

In Dubai his father was obsessed with cameras, he says, whether holding the camera himself or directing other peoples’ efforts to shoot. He would send these video postcards to his brother in the camp, who had a camera of his own and would return the favor.

“For me,” Fleifel says, “Ain al-Hilweh was better than Disneyland.”

A decade later, when Fleifel’s uncle ran the only sporting goods shop in the camp, he was there to witness Brazil winning the World Cup. During the Mondiale, Ain al-Hilweh – a space of one square kilometer that housed 70,000 refugees, “became the best place in the world to be.”

For that month, Fleifel recollects, while the camera lingers over a montage of international flags, team jerseys and other Mondiale paraphernalia, “residents cease to be stateless refugees and become Italians or Germans or Brazilians.”

“How can you cheer for Germany,” Fleifel’s grandfather grumbles, “when the Germans support the Israeli siege of Gaza?”

“I support Italy because once they dedicated their World Cup to us,” explains a young man named Abu Ayad. “So it’s our duty to support such a team.”

“I don’t care when it happened,” he continues. “I hate begin reminded that time is passing.”

The World Cup provides a happy framing narrative for the introduction of Fleifel’s friends Abu Ayad and Said. Along with the filmmaker’s grandfather, the two men are the film’s principal protagonists, and Fleifel unveils the complexity of their characters with all the care of a screenwriter.

Actually named Basam, Abu Ayad has assumed the name of a PLO operative who was assassinated overseas. He and the filmmaker have been close since 2006, the year his team won the cup and Israel went to war on Lebanon.

Abu Ayad has been with Fatah since he was a boy, which earns him an allowance from the PLO – enough money for coffee and cigarettes.

“The Palestinians really f**ked us over, man. I wish Israel would kill every last one of us,” Abu Ayad tells the camera. “We destroyed ourselves ... our revolution’s failed leaders, the thieves and the corrupt ... the cokeheads and the gamblers.”

Fleifel recalls his uncle Said as the only sensible man in Ain al-Hilweh, one not obsessed by muscles and displays of physical strength. He is actually not his uncle at all, but his granddad’s half-brother.

Along with his brother Jamal, Said was once the pride of the camp. Jamal died tragically young, however, and recently Said has become unpredictable, spending most of his time alone, tending his pigeons.

Said is unmarried and has never travelled outside Lebanon. He spends much of his time watching children’s television, or else Al-Manar or the occasional Adel Imam comedy. Now camp residents treat him like the village idiot.

“A World Not Ours” is about how existence in Ain al-Hilweh has sapped the vitality of two figures who have been formative influences for the filmmaker.

It is equally about changing perceptions of place – about how the naive perspective of a boy, hesitant to lose the camaraderie of the space, came to be altered by his experience of the outside world as much as his friends’ confinement.

While living in Denmark, Fleifel recalls having had an opportunity to visit Palestine.

“It felt so confusing,” he says, “as if I were visiting someone else’s country ... For me, Palestine was somewhere in Ain al-Hilweh.”