A conference on the much-anticipated role of Islamist political movements in a post-revolutionary Arab world promised to be a sombre academic affair. Speakers and attendees came from Tunisia, Morocco, Sudan, Jordan, Palestine, Egypt as well as Qatar, Saudi Arabia and the UAE. The discussions on the first day of the proceedings provided a rapid-fire introduction to the factors which make Islamist politics—so much a part of the revolutions which spread through the Arab region like wildfire throughout 2011—what it is: a tradition of exegesis going back centuries; a commitment to fighting foreign imperialism; and a modern experience of fighting domestic tyranny.

The meeting, hosted by the Arab Center for Research and Policy Studies, began promisingly enough with crowds coming in early on a weekend morning. ACRPS Director, the Palestinian intellectual Azmi Bishara, who always seems to have an intellectual arsenal at his fingertips, explained how it was feasible for Arab countries to become democratic and yet remain Muslim. Bishara went over the differences between intellectual histories between the Arab countries and Europe, yet there were also similarities. Comparable to present-day Salafists in Saudi Arabia, the Puritans who took power in England during the mid-seventeenth century were also “anti-fun” (not Bishara's words). Famously banning Christmas, they were also motivated—like the Salafists—by a desire to bring an end to “innovations” in religious practice. Perhaps the similarities between East and West didn't end there, either. Bishara went on to demonstrate, with the aid of data from public opinion surveys, that Arab respondents—16,000 of them—provided answers which would not be out of place in a Western country.

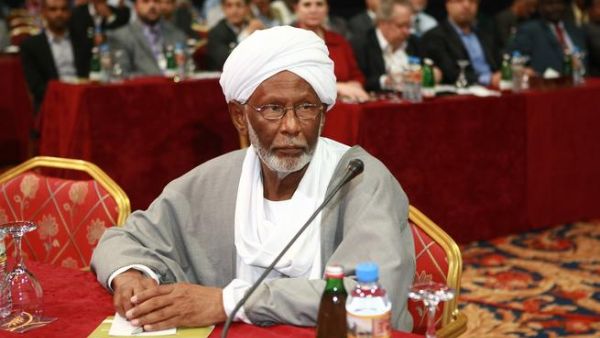

After Bishara's lecture, the assembled guests broke apart to listen to academic lectures on Shi'ite political Islam in Lebanon; the experience of Islamist government in Sudan; the rise to power of En Nahda in Tunisia and the question of armed Islamist groups in Yemen. Alongside the academics in attendance, the event also played host to a number of big-hitter Islamist politicians, adding a pragmatic flavour to the proceedings; Khaled Meshaal of the Palestinian group Hamas, and the now-influential Chiekh Rachid Ghannouchi of Tunisia’s En Nahda movement—ruthlessly persecuted by Zinelabidine Ben-Ali—are due to attend the final day of the Conference on Monday, 8 October. Participants who could only attend the first day, however, were in for a similar treat: a public lecture by Sudan’s Hassan al Turabi.

Turabi is an exceptionally controversial, enigmatic character. While in the opposition, he was credited with some of the Islamic world's most daring religious rulings (or “fatwas”): deeming it permissable for Muslim women to marry non-Muslim men, for example, or suggesting that drinking alcohol could be acceptable in certain conditions. Going out on a limb, he was one of few who openly declared that Salman Rushdie did not deserve the death penalty for his novels. Sounds like the progressives' friend? Yet it seems that there were two Turabis.

Coming to power vicariously during the rule of the junta led, since the 1960s, by Jaafar Nimeiry, Turabi—previously an exiled Islamist opposition member—rose to be Minister of Justice, and oversaw a brutal regime of executions, amputations and lashings. More menacingly, some of those whose executions which were sanctioned by Turabi were clearly politically motivated, and they worked. They worked, that is until Turabi was removed by the country's first democratic elections in decades, held in 1985.

Giving democracy just enough time to breathe, Turabi worked with another military officer—Omar Hassan Al Bashir—to grab power anew, now in 1989, bringing in another reign of military-Islamist terror. Oddly enough, disagreements with Bashir—still sitting in power in Khartoum—led to Turabi being let out on his backside, after a further stint in jail. Surely, there was a lot in all of these experiences to fill in a one-and-a-half hour slot in Doha with lots of excitement.

Turabi could easily have been expecting an easy ride at the Doha Sheraton—a cosy welcome for an interesting if controversial theologian and former politician, and an octogenarian to boot. He certainly gave the impression that he was feeling welcome—for two, soporific hours, he went on to expound on the intricacies of his very colourful personal life, telling a bemused audience about how he worked amongst the Muslim migrant communities in Paris and in London during his time as a student in the US, England and France. All the while, he laughed unexplainably. After Turabi ended his pontification, the first indications that the questions from the floor were going to be reassuringly compliant. Then the bombshell came.

Khaled Hroub, a famous Palestinian media scholar and broadcaster who used to host a book show on Al Jazeera in times gone by, wasn't having any of it. “You promised to give us a candid disclosure of your life path” but “instead, you have given us a paean worthy of Castro or Chavez. What do you think you're doing?”. With the audience suitably awed and silenced, Hroub went on to ask to-the-point, probing questions of the geriatric Sudanese public figure: “I remember seeing you in Sudan in the 1990s. I was a young man then, and you were giving rousing speeches building momentum for the jihad in the South of the country. What do you have to say about the youth who died in that war? What responsibility do you take for their deaths?” Hroub, who used to be an Islamist activist while a student in Jordan before his Damascene moment, seemed to be reading the minds of many in the audience when he insisted “we've had enough of these kinds of diatribes, we expect you to take some responsibility”.

The applause, although silent, could be felt. Of course, when one famous personage takes on another, you can expect something to come of it later—this is likely going to be a big-time spat between two large-ish intellectual figures on the Arab scene, maybe something worthy of the two Hitchens', but with more teeth. The Arabs have yet to pull off the hat-trick of balancing democracy with Islamism, but Hroub's brave intervention is an example of how the urgency and immediacy of the Arab Spring are making themselves felt in intellectual debate.

By Samer Walid, a freelance journalist living in Doha.

Share your views on the tension or indeed new marriage coupling Islamism with democracy in this new Arab Spring age: Are old mistakes going to be repeated or will the new Islamists be just what the doctor ordered for the region?