The Complete "Story of Star Wars":

Part 1: "Out of the Past"

Part 2: "Annikin Starkiller"

Part 3: "A Cohesive Reality"

Part 4: "A Desert Planet"

Part 5: "What a Load of Rubbish"

Part 6: "Darth Farmer"

Part 7: "Binary Sunset"

***

Star Wars was going to fail.

The shoot had been a nightmare. The cast and crew derided the work, dismissing Star Wars as a “kid’s film”—and not a very good kid’s film, either. Key actors thought the script something of a convoluted, pseudo-philosophical mess. The dialogue was stiff and wooden; one cast member would famously proclaim he couldn’t say any of it. The film had gone $3 million over-budget. Props broke down; costumes wouldn’t fit together properly. A freak rainstorm—in the middle of the Tunisian desert, no less—delayed the filming of several key scenes, bloating costs.

Standing in the eye of the storm was the man who had written and directed this production. His confidence, too, was failing.

***

Star Wars exists because George Lucas had failed.

1971 was a different world. A wave of smaller, independent films was taking over the American imagination: grittier fare, independently produced and more innovative. More importantly, they were a reflection of American counterculture, stripped of idealism and heroes and fuelled by a more cynical, pessimistic outlook. “The New Hollywood” came to life with films like Chinatown (1974), Bonnie and Clyde (1967), and Easy Rider (1969), statements in a world where Kennedy had been killed and the Vietnam War was destined to rage on. Humanity’s gaze had turned back to Earth, the Space Race dying in the desert lands of foreign policy.

The decline of classic Hollywood meant that studios were looking at film schools in hopes of hiring directors whose work could connect with an increasingly important demographic: youth. At the forefront were artists like Martin Scorsese and Brian De Palma—artists who’d bring a personal touch to their work.

Riding this wave was one George Lucas, who’d left his hometown of Modesto to attend film school at the University of Southern California. He was working as an assistant alongside another aspiring filmmaker—an obscure talent named Steven Spielberg—on Francis Ford Coppola’s The Rain People (1969).

They were both skinny, bearded men, with big, awkward glasses on their faces and a love for the old movie serials they’d grown-up on. They shared certain sensibilities and were a good match, professionally—it helped that they were good friends, too.

The two were encouraging their friend John Milius to write a Vietnam War film. Milius took them up, pursuing the material he needed in Joseph Conrad’s novel Heart of Darkness (1899).

When The Rain People wrapped, Lucas began working on his own feature, a science-fiction story produced by Coppola called THX 1138 (1971). It was an adaptation of his own 20-minute long student project, created with little money and on a tight schedule.

Co-written with Walter Murch, THX 1138 is a product of the cynicism of its time. It is set in a bleak dystopian future where feeling is outlawed and human beings are subject to emotion-suppressive drugs; sexual desire is illegal. The law has an iron fist, slammed down by a squadron of android police.

Above: A still from THX 1138. (Warner Bros. Entertainment Inc.)

Despite the critical reputation it now enjoys, the film’s pessimism and low production values earned it a mixed critical reception. Its box office returns didn’t exactly turn heads in Hollywood, either.

So Coppola challenged Lucas to come-up with something that would appeal to mainstream Americans: what Lucas would describe as a “fuzzy comedy.” Lucas was enthusiastic: “[THX] was about real things that were going on and the problems we're faced with,” he would later reflect. “I realized after making THX that those problems are so real that most of us have to face those things every day, so we're in a constant state of frustration. That just makes us more depressed than we were before. So I made a film where, essentially, we can get rid of some of those frustrations, the feeling that everything seems futile.”

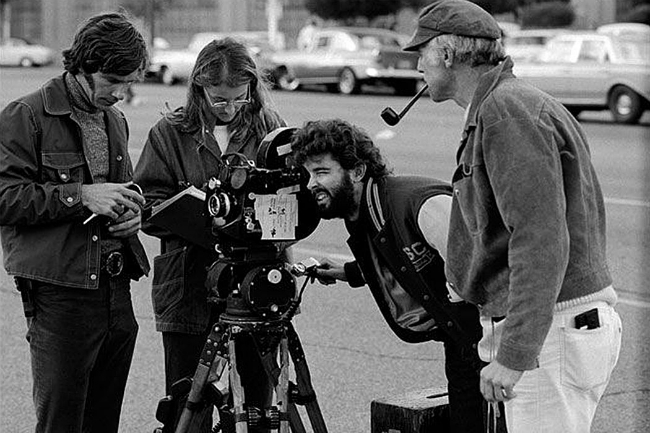

Above: George Lucas filming American Graffiti in 1972. (Lucasfilm)

THX 1138, meanwhile, had brought in offers to direct other projects, including what would become Hair (1979). Lucas turned these down—even when Warner Bros. shelved his Vietnam War film—feeling that the films he’d rather make would be his own. In the wake of the Vietnam project’s failure, he kept developing the “fuzzy comedy”—and began imagining a space opera on the side.

Things began to look upwards at the 1971 Cannes Film Festival. THX 1138 was chosen for the Directors’ Fortnight competition, which lead to a meeting with the president of United Artists. The two men talked about Lucas’s two projects. It lead to a $10,000 two-picture deal for both the space opera and the other film, called Another Quiet Night in Modesto.

Lucas would draw on his teenage years cruisin’ in Modesto, California, to write the script, the same place he would set the film. It would be an accurate representation of the way boys in that time and place would try meeting girls.

But Lucas got too ambitious. In his enthusiasm, the film was written to include no fewer than 75 pieces of licensed music. The script struck United Artists as too experimental—something like a musical homage to a bygone era. They dropped the project.

Lucas took matters into his own hands and created Lucasfilm Ltd. in San Rafael in 1971. Never again would he be subject to the whims of a studio, he decided. He would sit down and develop Modesto properly—the way he wanted.

It would eventually find a home at Universal Studios, developed, rewritten, and finally releasing as American Graffiti (1973). The film, shot over 28 days for under a million dollars, is a series of vignettes based around a crazy crew of cruisin’ car enthusiasts, loosely based on actual events. It was hugely profitable—and subject to fawning critical acclaim. Today, American Graffiti (starring future Academy Award-winning director Ron Howard) is considered a classic.

Which left the little matter of the space opera.

Above: A poster for THX 1138 (Warner Bros. Entertainment Inc.); below it, another for American Graffiti (Universal Pictures)

NEXT: "Annikin Starkiller"