The Complete "Story of Star Wars":

Part 1: "Out of the Past"

Part 2: "Annikin Starkiller"

Part 3: "A Cohesive Reality"

Part 4: "A Desert Planet"

Part 5: "What a Load of Rubbish"

Part 6: "Darth Farmer"

Part 7: "Binary Sunset"

***

The film’s editing room had been empty for months, and the footage Jympson had cut needed to be restored to dailies form to allow the new editor to start over.

Richard Chew came to the project recommended by Coppola: he’d been the editor on The Conversation (1974). With him came Marcia, now Lucas’s wife of eight years. She had become a professional film editor, earning the trust of Martin Scorsese—a face of the “New Hollywood” who had, by 1977, secured his reputation as a master filmmaker with works like Mean Streets (1973) and Taxi Driver (1976), the latter of which she’d edited. She’d also been nominated for an Academy Award for Best Editing—for American Graffiti, no less. She came to Star Wars as a loan, released from Scorsese’s new film New York, New York (1977) for several months as a favour.

Above: Marcia and George Lucas in the editing room. (Life)

It became quickly apparent that the workload was too high; the editors were staying-up until early hours of the morning cutting footage. Marcia was forced to bring in Paul Hirsch, who De Palma had recommended. Hirsch had edited several of De Palma’s films, including Sisters (1972), Phantom of the Paradise (1974), and Carrie (1976)—the film whose casting had taken place alongside that of Star Wars.

As the editors saw it, the problem with Jympson’s cut was that he had let too much happen at too slow a pace. The film was salvageable, but it required a certain kinetic energy which this cut didn’t have.

Jympson’s cut was dictated by the actors’ movements, as opposed to letting the rhythms of the film be driven by the cuts. So if Hamill took his time to respond to a line, the cut would simply wait.

The editors got to work, alternating between reels to grab footage as they finished editing one thing to move onto the next one. They often cross-cut takes to get the kind of pacing they needed. At times, they improvised. In one scene at the beginning of the movie, Luke is ambushed by a Tusken Raider, a member of a tribal, Bedouin-like race of nomadic warrior “sand people” who knocks him unconscious and then raises his weapon over his head in triumph.

“He just did it once,” said Hirsch, “and we rocked it back and forth so he did it a number of times.”

It’s the kind of good editing a director hopes for.

They also cut-out several scenes at the beginning of the movie, realizing they overburdened an already complex script. As such, a scene where Luke notices two ships engaged in combat as he repairs a droid in the desert? Cut. A scene where Luke meets his friends in Anchorhead to tell his friends about the fight and where he almost runs over an old woman? Cut. A scene where Luke and C-3PO discuss the unfolding narrative as they search for R2-D2? Cut. Biggs Darklighter, Luke’s friend, who is played by Garrick Hagon? Mostly cut, and reduced to a small role at the end of the film. (One shot, in which a gun on the Millennium Falcon fires at Stormtroopers, was dropped only to end-up in the sequel, 1980’s The Empire Strikes Back.)

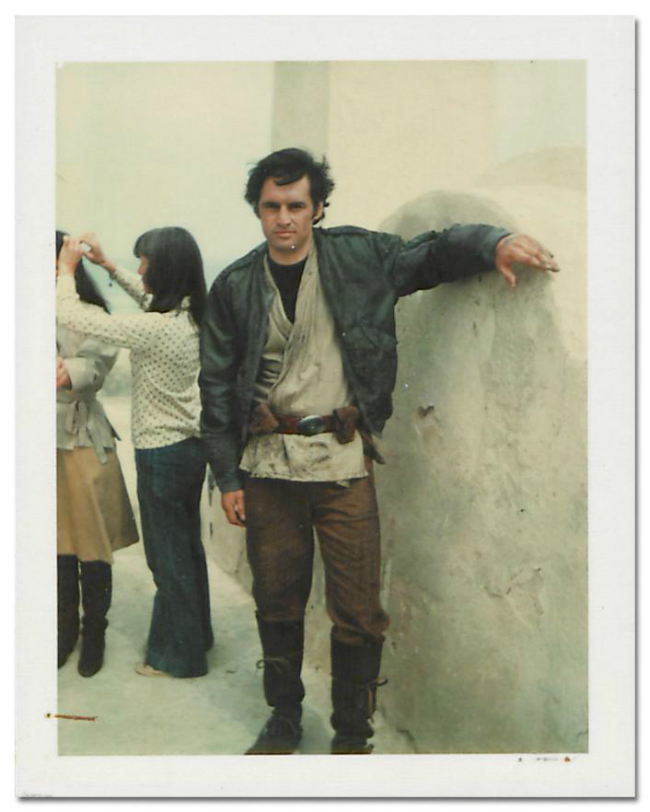

Above: Anthony Forrest as Laze Loneozner, Koo Stark as Camie, Garrick Hagon as Biggs Darklighter, cut from the film (except for Biggs, who gets blown-up at the end). (Ann Skinner / Lucasfilm)

Some of the cuts were practical. The editors decided that establishing daily life on Tatooine would reduce narrative drive: the heart of the first act was getting the droids to Luke; establishing Luke’s character would have to wait until the plot required his appearance. Focusing on the robots was a risk, but a necessary one. Another was cut because the crew simply didn’t have the budget for it in post-production: Han Solo’s conversation with Jabba the Hutt—imagined as a sort of bipedal, furry alien gangster—in Mos Eisley Spaceport.

Often, scenes were trimmed down for pacing: in one, the camera follows a patron of the Mos Eisley Cantina outside and watches him tip-off Stormtroopers about Luke and Obi-Wan Kenobi’s presence there; the scene is reduced to a single shot in the final film.

Lucas, meanwhile, assembled dogfight footage from World War II films. He returned to The Dam Busters, cross-cutting scenes from the film with scenes from 633 Squadron (1964) to showcase the pace he wanted the film’s climax to run on.

***

In February of 1977, with release just three months away, Lucas screened a new cut to Twentieth Century Fox. Also present were Marvel Comics employees preparing to make Star Wars into a comic book—part of the film’s marketing efforts—as well as some friends and figures who’d helped Lucas reach this point.

This was going to be a rough screening—in place of the film’s climactic sequence, Lucas was using the dogfight footage he’d assembled, interspersed with footage from the film. But the pieces were there, the story more or less intact.

The curtain rose to a deathly silence, interrupted only by Martia’s muffled sobbing. The film was awful, she thought: “The At Long Last Love of science fiction.”In fact, almost none of the artists present had enjoyed it; De Palma just called it cheesy.

There was, however, a notable exception to this bemusement.

Steven Spielberg had come a long way since The Rain People. He’d gone to work in television, making a film called Duel (1971) impressive enough it received a theatrical release. He’d followed that up with The Sugarland Express (1974), which won Best Screenplay at the Cannes Film Festival, and then Jaws (1975), the world’s first mega blockbuster. He’d received his share of critical praise, too; Alfred Hitchcock, the iconic director behind efforts like Psycho (1960), was effusive.

Above: Producer Gary Kurtz, De Palma, editor Paul Hirsch, Spielberg, and Lucas after the screening.

Lucas had visited Spielberg on the set of Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977), nervous about the future of Star Wars. Lucas was amazed by what he saw: he’d visibly exclaimed his astonishment at the work Spielberg had put into his science-fiction film, bowled over by the results and proclaiming that Spielberg had another mega-hit on his hands. Spielberg tried and failed to set his friend’s mind to rest, confident that Star Wars would do well. Lucas didn’t take, instead proposing a trade-off: what if Lucas got 2.5% of what Close Encounters made for Spielberg and traded away an equivalent percentage of Star Wars? Spielberg agreed.

Spielberg hadn’t just liked Star Wars; he suspected it would actually be a hit, and said so. Studio executives agreed; one, Gareth Wigan, had been so overwhelmed by it he’d actually wept, and had later sat his family down at the kitchen table to share his experience with them. This surprised and humbled Lucas, whose films had traditionally been dismissed by executives.

As it stood, the lukewarm reaction was probably due to missing special effects; blaster fire, for instance, was depicted as hand-drawn arrows.

Issues were ongoing at ILM. This was a problem Lucas needed to fix.

***

In more accurate terms, the situation at ILM had become catastrophic.

Between McQuarrie’s fee and ILM, Lucas had spent approximately $473,000 of his own money on Star Wars on preproduction. This had netted him a total of four shots, none of them usable, and half the budget spent.

ILM had known what they were going for, and they were going for uncharted territories. Star Wars, they said,had required inventing new technology and techniques. But Fox had become furious; they accused ILM of lacking discipline.

Dykstra maintained that the crew hadn’t slacked off; ILM had needed to build the tools—optical printers, motion control cameras—it would use to make the shots, and had needed to set-up shop. The studio included a carpentry shop, a machine shop—used to build or modify the cameras and editing and animation equipment required for the special effects—and a model shop.

They had, for example, built a motion control camera to work without a loader or operator. The Dykstraflex—after Dyskstra—was built from old VistaVision cameras (chosen for their large picture size) to move in seven different axes of motion. The Dykstraflex could roll, pan, swing, tilt, traverse, track, and do lens focusing and shutter control. It could, therefore, repeatedly perform complex motions around stationary models, making it that much easier to duplicate a shot for two different models. This was huge; when you could repeat a camera movement between two ships, you gave the impression—for example—that they were in a chase.

Above: The lightsabers as they appeared on-set. (Lucasfilm)

Above: The Dykstraflex. (Lucasfilm)

It was good work, but Lucas had to intervene. The film’s special effects were its key, and ILM had three hundred and sixty uncompleted shots to complete, with only six months to complete them.

Lucas set-up a production team at ILM, created to enforce a quota; he personally went to the studio twice a week. The team did resent this somewhat, feeling the new system was intrusive; Dykstra compared ILM’s mentality to that of a country club’s.

Seventy-five people threw themselves into the visual effects work, coming in two shifts. The crew contrasted the spaceship models against blue screens backlit with fluorescent lights, using chroma keying to compose the images of the spaceships with the space backgrounds. They went with a horizontal 35mm double-frame camera format, which allowed a negative print large enough to work with the live action footage. Better yet, they had figured-out how to run the fluorescent lighting on alternating current instead of direct, which meant that any shots taken at high-speeds wouldn’t be subject to flickering.

They’d built a huge Death Star model on the ILM parking lot, driving past it with cameras attached to the backs of trucks or hovering over the model with a crane to get the “zooming” footage of a spaceship attacking the Death Star.

Above: The ILM team at work. (Lucasfilm)

The dogfight cuts came in handy here. It allowed ILM to superimpose the footage so they could imitate the shots and angles; more importantly, the footage reflected the rhythms, speed, and energy these shots needed.

***

Visual effects were one thing, but choosing the right sound for the picture mattered.

Ben Burtt had spent the production imagining. Lucas had told him he’d wanted an “organic soundtrack”—part of the cohesive reality he was building—and Burtt was up for the challenge.

So for the lightsabers, Burtt had gone for an “electric” sound—the kind that would make a person’s arm hair stand on end. He achieved this by using a shieldless microphone to record TV interference, which he layered on top of the motor hum of an old movie projector. Vrrrmm, it murmured. Chewbacca, whose lines in the movie were delivered by Mayhew, was overdubbed by a careful mix of animal sounds; Burtt created phrases and noises from the roars and growls of tigers, lions, walruses and bears, trying to give the impression of a consistent language.

Above: Ben Burtt records a bear. (Lucasfilm)

R2-D2 was another challenge. Burtt first tried using an electronic synthesizer to create what the script described as the droid’s “whistles,” but the results weren’t satisfactory. Burtt did kind of associate R2-D2 with a toddler, though. Imitating a baby’s “boops” through an electronic synthesizer gave him the result he wanted, finally adding to the “happy droid” aesthetic Baker and Lucas had striven for.

It was Darth Vader that needed to work.

Darth Farmer was still a problem. Prowse, for all his height and presence, was never going to be the final voice of Darth Vader, but he had delivered the lines on set and the actors had reacted to it with disbelief. They needed a dark, commanding voice for their dark lord.

Above: On the right, David Prowse appears on set, Vader mask off. (Lucasfilm)

Lucas had spent production hoping that Orson Welles, a renowned director and actor, would lend his voice to Vader; Welles was known for his beautiful, iconic bass baritone, heard in a widely acclaimed stage, film, and radio career.

But that was the problem—Welles was an icon, and therefore instantly recognizable. Lucas instead cast a classically trained stage and film actor, James Earl Jones (amazingly, a stutterer in his childhood), chosen for the timbre of his voice.

To complete the effect, Burtt added a small microphone into a scuba tank’s regulator, then breathed into the scuba mask. Darth Vader’s belaboured breathing was the result of the air expanding and contracting against the walls of the regulator. The outcome was unsettling.

NEXT: "Binary Sunset"