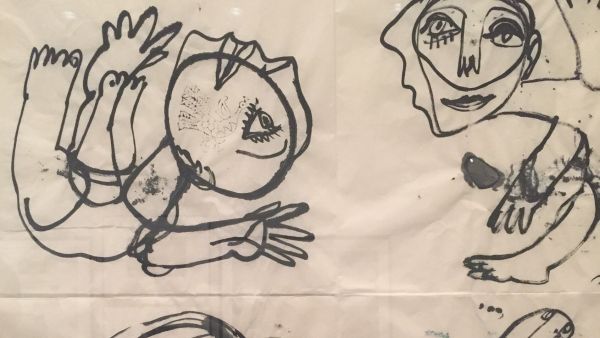

A hazy, almost impressionistic image of a horizon. Charcoal sketches of bottles and flowers.

Tiny disembodied bird legs, all perched in a row. “Towards the Sublime,” curated by Galerie Tanit’s Naila Kettaneh-Kunigk and Mayssa Abou Rahal, brings together the diverse production of 17 local and international artists. Some artistic works will be new to viewers. Others will be familiar, but evoke fresh readings in their new context.

The theme of this year’s iteration of Tanit’s annual group show, the curators said, was born of the idea of exploring transparency, transcendence and light.

“Slowly we discovered that the show was not really just about transparency and transcendence,” Abou Rahal said. “It was about more, and there was a lot of strength in it. The idea of strength for us was very philosophical. It was very also emotional.”

Contemplation of the sublime dates back to ancient times. The gallery cites the perspectives of 18th-century philosophers Edmund Burke and Immanuel Kant, with ideas ranging from pleasure and reason to vast might and “delightful horror.”

Viewers familiar with Burke and Kant can observe various facets of their discussions of the sublime within individual pieces. But the exhibition is not heavy with history or taxing theoretical discussions. Instead, it emphasizes the aesthetic and the viewer’s experience of the works.

{"preview_thumbnail":"https://cdn.flowplayer.com/6684a05f-6468-4ecd-87d5-a748773282a3/i/v-i-4…","video_id":"49174369-ee74-4b64-b12a-9f51b99a8580","player_id":"8ca46225-42a2-4245-9c20-7850ae937431","provider":"flowplayer","video":"UK Rule Out Swapping Seized Oil Tankers With Iran"}

Several of the pieces have an immersive or meditative quality. Photographs by Lebanese artists Ziad Antar and Gilbert Hage feel otherworldly, infinite. Lamia Joreige’s “Ouzai, Cartography of a Transformation 4, 2017,” from the series “Under-Writing Beirut,” makes a similar impression, yet also conveys something more sinister as the edges of the aerial landscape disappear into a white haze.

Elger Esser’s black-and-white images show more tangible subjects and contain elements that refer directly to art history and religion. One picture of a church interior evokes reflection on the role of the church and sacred texts in experiences of awe and terror.

Nabil Nahas’ painting has a branching cedar tree as its central form, while brushes of gold add a daub of royalty and referring back to art history, Abou Rahal noted.

“Nabil has worked with the idea of the religious sublime,” Kettaneh-Kunigk said, but doesn’t restrict himself to that. His “Untitled” work “has an incredible strength towards the top, towards going somewhere, and it’s abstract without being totally abstract.”

Nahas’ work also alludes to the power of nature, as does work by Daniele Genadry and Abed Al Kadiri.

Others spring from darker places. Syrian artist Fadi Yazigi’s “Untitled,” 2013, is an art installation of 20 tiny birds’ legs, perched without bodies in individual plexiglass compartments.

“I brought it with me from Damascus,” Abou Rahal said. “I felt that it was horrific, but at the same time it’s so strong ... When the theme changed, it was radical to have it. It’s terror. It’s fear and it’s death.”

One of the legs of Ayman Baalbaki’s fierce glass and wood installation “Cheveaux de Frise: Homage to Apollinaire” broke during installation, and the artist decided to leave it that way. This sparks different readings of the piece, after (or perhaps thanks to) the initial shock of seeing the violence of the damage.

Walid Sadek’s at first apparently anti-sublime work (don’t miss it in the corner) is a papier-mache piece that looks like it’s made of cement, presenting an immediate paradox of ephemerality in its materiality. Abou Rahal noted the conceptual, physical, artistic contrasts that the small piece offers.

“It was essential to have Walid Sadek in a show like that,” she said, citing the Lebanese artist’s tackling of philosophical issues. “He chose the corner where it would be, and he didn’t want to have anything that would highlight it.”

German-based South Korean artist Bongchull Shin’s works are the embodiment of transparency and light. The installation of neat, colored, angular glass pieces shares a geometric element with Yazigi’s work, but the piece is Zen in its installation and disarming in its simplicity. It also has a hidden dynamic component. Abou Rahal said that after hours, the light hits the work at a particular angle and the colors reflect across the gallery walls.

“Towards the Sublime” provides a moment of contemplation and a space to breathe. It draws audiences in through the aesthetic of the pieces and the ability of many of them to immerse viewers in a moment of conscious or subconscious contemplation.

“We wanted to do something that was not political,” Abou Rahal said, “that brought back the essence of art. In the beginning it [art] was about beauty. It was about feelings. It was about more than just conceptual, political art, that is all over the place” nowadays.

“We wanted to present an environment that really cut you out from everything that’s happening in the region and the country and in daily life,” she added.

“The country’s going through an economic crisis. You’re surrounded by wars. You wake up in the morning with a ton of negative energy.”

“So we thought it would be good to give some good news,” Kettaneh-Kunigk reflected.

“Yeah, something to come in and relax and enjoy and feel,” Abou Rahal added.

“That’s what we wanted.”

This article has been adapted from its original source.