Wedged among construction sites, crouching beneath a new tower, a two-story house is slowly falling into ruins. The red-tiled roof, arcades and outdoor staircase are intact, but the uninhabited edifice is a skeleton, with marble tiles, wooden panels and other debris scattered about. If you ask anyone in this part of why this house is important, the chances are that they will answer: “Fairouz.”

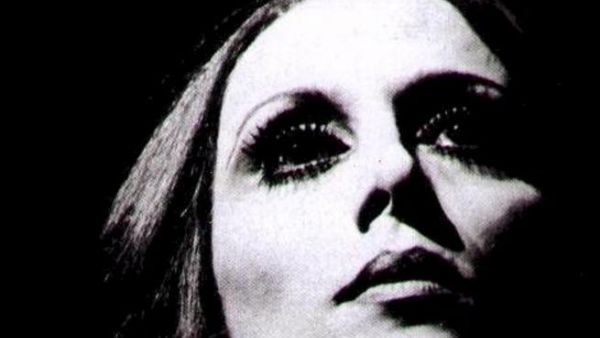

Lebanon’s best-loved musical icon, Fairouz (née Nohad Wadi Haddad) is as renowned for her outstanding, and remarkably adaptable, voice as for the engaged lyrics of her songs – whether composed by the Brothers Rahbani or her son, Ziyad Rahbani.

When she was still a girl called Nohad, Fairouz lived in this modest Zoqaq al-Blat house.

It has been more than three years since Beirut Municipality announced it would restore the house into a museum devoted to the legendary vocalist’s life. Yet when Mayor Bilal Hamad spoke to The Daily Star about the state of this project recently, he said the restoration was taking more time than they had planned.

“It took some time because of the expropriation law,” he said, and also “because of the condition of the house.”

Hamad gave no further details as to what the planned museum would look like – whether the façade would remain as is or would be restored – or how it would function.

It’s also unknown whether the space will exhibit a fixed collection of objects and recordings or also host secondary shows, devoted to other Lebanese or Middle Eastern musicians.

Hamad said the municipality was waiting for the governement’s approval before moving ahead with its plans for the house.

To this point, the municipality seems to have assigned a man to guard the house in order to prevent anyone from entering. Hamad said he hoped to preserve Fairouz’s house to the maximum.

It appears the municipality’s project is bound by the “Construction Law of 1983,” which regulates the restoration or enhancement of historic sites and structures for use as artistic and cultural spaces.

“We will coordinate with [the performer] on the final aspects [of the conservation],” he said, adding that the municipality had decided to finance the house repair itself.

Beirut Municipality has other architectural restoration projects of this kind. Beit Barakat, a uniquely designed multifamily dwelling adjacent to Sodeco Square, transformed from gracious residential accommodation to a snipers’ nest overlooking one of the civil war-era’s east-west crossing points.

Working in partnership with Paris Municipality, this city’s authorities are transforming the structure into “Beit Beirut,” a museum and cultural center. The project is meant to be an homage to the Lebanese Civil War.

Another restoration project has been discussed for the mansion of Lebanese poet Bechara al-Khoury.

A far more grand structure than Fairouz’s, the Khoury house’s arcades – long amputated from its once-extensive gardens – tower over the southern extremes of Zoqaq al-Blat.

Though the structures are quite unlike one another, the Bechara al-Khoury and Fairouz houses both belong to the historic urban fabric of Zoqaq al-Blat and the lingering cultural legacy distilled there.

The neighborhood is dotted with notable households, but only a few are still lived in. Some are employed as schools and one villa houses the German Orient Institude (OIB), a state-funded research facility. Most of these buildings are likely to be razed.

If both the Khoury and Fairouz houses are renovated according to plan, they will be exceptional in Beirut, insofar as most of the city’s public monuments honor politicians rather than celebrated cultural figures.

Cairo-based architectural historian Ralph Bodenstein knows the former Fairouz residence as well as anyone. Between 1997 and 2003, Bodenstein worked with a team of researchers at the OIB to survey the histories of Zoqaq al-Blat and the changes to its urban fabric.

“Together with the building on the right [pictured left, today in ruins] and the single-story annexes with courtyard and trees in front of it,” Bodenstein told The Daily Star, the structure “served as an Ottoman police station in the late 19th century.”

The old police station was converted to residential housing at the beginning of the 20th century, he said. The second story with its red-tiled roof was added later still. It is not known who designed or built the house, and there are no clues whatsoever about its first residents.

When The Daily Star went to see the childhood home of the country’s greatest living musical icon, the structure itself was much less conspicuous than the Lebanese Army soldiers and troop transports stationed in the neighborhood. The narrow passage leading to the old house was blocked by cement barricades and improvised metal gates.

To enter the house one must climb a fence and navigate a clutch of trees, a neglected garden and stone alleyway. The Haddad family (Fairouz included) resided on the house’s ground floor.

Today it looks as though a bomb went off there.

Broken walls contain derelict furniture – including the headboard of an abandoned bed – presumably the belongings of families who lived in the house long after Fairouz’s departure.

An exterior staircase gives access to the house’s upper floor, which was added later. Unlike the ground floor, there is no evidence of arcades or ornamentation, simply poured concrete. Like so many structures in Beirut – and like the city’s urban fabric generally – the house was a work in progress, with additional spaces added when needed.

The worth of this house, Bodenstein said, resides less in its grand or unique architecture than in the fact that it “is part of the historical neighborhood community of the area.”

For Bodenstein, the restoration initiative is a good one. Highlighting the courtyard in front of the house that used to link the buildings to one another, he said the initiative ought to take adjacent buildings into consideration as well.

Bodenstein said the house itself was probably too small to work as a museum. Further reason, he said, for the adjacent structures to be added to the museum initiative.

“They should maybe also take into account the annex buildings,” he observed, Fairouz’s house “is not a single structure but belongs to a complex. It will be very important to implement a project like this.”