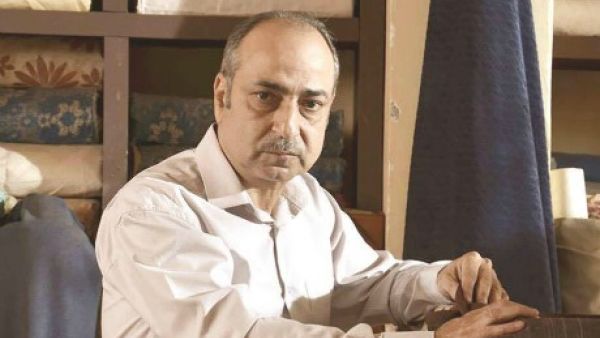

Born in 1959, Ahmed Kamal is one of the most notable Egyptian actors of his generation. His career began in the 1970s, and he has since worked in theatre, television and cinema, cooperating with the many distinguished Egyptian directors and writers.

Kamal also has a rich portfolio of work as an acting trainer, and supports many young filmmakers by participating in their films.

Ahram Online (AO): You just won the best actor award for your role in short Wintry Spring (Rabie Chetwy) at the 48th Fotogramma d'Oro Film Festival in Italy. Directed by Mohamed Kamel (who won the best film award at the same festival), Wintry Spring participated in numerous international film festivals and won several awards. Did you expect the success?

Ahmed Kamal (AK): The film is about the relationship between a father and his teenage daughter, and the changes she faces in the absence of the mother. I don't think this issue has ever been tackled in our films.

I could tell it was a great film the moment I read the script. It is also very well written by Tamer Abdel Hamid in cooperation with the director Mohamed Kamel. It was a team of professionals with a young director who knows exactly what he wants to do and puts a lot of effort into the pre-production and distribution. The director did not have any company to support him, even in the distribution phase, or to facilitate the film's participation in all of these film festivals.

AO: Your biography includes working with dozens of big names in theatre and cinema. Yet you still participate in short films by young filmmakers.

AK: Working with young filmmakers gives me fresh insight. I like the way they think; they are smart and more daring in comparison with our generation. They take me to a different world. But at the same time, I believe that we should always give a hand to such young filmmakers.

AO: But isn’t there an element of risk involved, something that other established actors might fear?

AK: Remember that a good director would not accept a bad script. I am careful in my selection too. If I like a script, I meet the director to understand his vision. I do not work for money; it has to be a good film and an interesting role. I love acting yet I would not make an artistic compromise.

AO: You have worked with many renowned directors of different generations: Daoud Abdel Sayed, Khairy Beshara, Mohamed Khan, Yousry Nasrallah, Ali Edris, Khaled El Hagar, Kamla Abu Zikry, Hala Khalil. Some you worked with more than once. Tell us more about this rich experience.

AK: Each director has his own personality, but all the good directors share some core principles: they have profound knowledge, they study the script well, they have clear vision but are flexible on location. On the other hand they talk little, do not shout, have their time of silence and meditation. This applies to both men and women; both share the same feeling of responsibility. They are all very professional -- fighters working long hours.

As an actor, you always build trust, mutual understanding and respect with a director; become familiar with their methods. As a professional actor I need to understand my role while respecting the vision of the director.

AO: Haven’t you though of directing yourself?

AK: In Egypt it is a very tough job. Many directors lead a miserable and very stressful life. That is why they had a hard time learning to be very calm, and they even become their own psychotherapists, so they don’t go insane! I don't have the energy and patience for that.

AO: You have worked in Egypt’s film industry for several decades. How would you describe the changes taking place in this field?

AK: I would prefer to talk about cinema, theatre, and television altogether. Starting with the mid 1970s, we witness the rise of consumer culture, a fact that was topped with the migrations to Gulf. Many things started collapsing in Egypt in general and in the arts specifically. Then we had 30 years of the Mubarak regime, marked by the deliberate efforts to destroy the cultural institutions and ruin the artistic scene. Artists were struggling with all kinds of obstacles, even if despite all this, many managed to succeed, more or less.

The 2011 revolution shook the art scene as it did with the whole country. The competition is increasing; young artists have to study more to face the challenge, especially as we have many actors and not enough productions. On the other hand, the digital facilitations empowered short film production. So in general, I think the productions are improving.

AO: One of the first roles that brought you to limelight was in Daoud Abdel Sayed’s Kit Kat (1991). Do you consider this film a turning point in your cinematic career?

AK: I am originally a theatre actor, and I wished I could work in theatre all my life.

Later on, in the 1980s and 1990s, I had many important roles in independent theatre. I worked in Hassan El-Geretly’s El-Warsha troupe, as well as in theatre productions directed by Ahmed El-Attar, Nasser Abdel Moneim, Essam Essayed. These were among important stages in my career, and theatre was the best school for me.

The television roles came starting late 1980s. I worked with great writers, directors, and actors. I was very lucky. Then, I entered cinema and worked with many talented directors. Again, I was lucky.

I see all my roles as important and I work hard in each of them.

AO: Speaking of theatre, most recently you perform in Men El-Qalb lel Qalb (From Heart to Heart), a poetic adaptation of The Little Prince by Fouad Haddad, staged at the National Theatre. Tell us more about it.

AK: I loved the whole experience: Fouad Hadad’s poetry and this adaptation, Roushdy El-Shamy is a very creative director, just as Hazim Shahin as a composer. It is a simple and very cheerful work that I enjoyed a lot.

Egyptian theatre went through many low points and I think in recent years we see it’s interesting revival, not only the state theatre, but also there are many good young independent theatre troupes.

There are new and very fresh artistic trends which started with the 2011 revolution. On culture level, we owe this return of art to the revolution, and this not only in theatre but also cinema and television.

AO: What do you mean by new trends?

AK: The revolution challenged certain routine in arts. Now we have more daring works and new ideas. Young artists who participated in the revolution are actively enriching the artistic scene. They said enough is enough and we want to start a new life and a new page.

Despite the crisis, corruption, political confusion, I would say that on the level of cinema, theatre, and television, there are clear signs of improvement in terms of quality. They develop even further, I believe.

AO: Do you prefer the stage or the camera?

AK: I love a good role, it doesn’t matter if it’s theatre, film or television series. Each actor enjoys a good role and suitable production conditions.

In terms of conditions they involve a variety of elements. For example, shooting outdoors in Egypt can be challenged by outside factors. The producers need to invest in protection of the crew during shooting. Otherwise it can be very tough to work.

Another aspect would be advertisements. For instance, some theatres face production problems in terms of advertising, and people do not find out about the plays being performed.

If those problems are not solved, they can ruin the joy of the artistic experience.

AO: In your long career, you took dozens of different characters on your shoulders. How do you prepare for each of them?

AK: I like a character that is different from who I am. I also like characters who have depth, their own secrets, ambitions, pains, crises, and so on. Those elements encourage me, trigger my creativity.

On a practical level, I read my role 30 or 40 times at home, like a student. I experiment with many methods of becoming this or that character; I look at the different situations and try to find out how the character would react in such or such circumstances.

AO: And when you teach in acting workshops, what is the main advice you give to young actors and filmmakers?

AK: Everyone has his own journey. Broadly speaking, you do not follow certain rules to become a filmmaker or an actor. Everyone learns in his own way. There are artists who received certificates from the USA or other countries and they know nothing, and there are self-taught artists who do a great job.

For example, look at director Amr Salama, with whom I worked in the film Asmaa (2011). Salama is a self-taught filmmaker who mastered scriptwriting, editing, shooting and directing. Of course there are also The Film Academy graduates and they are very good as well.

What I tell my trainees that in all circumstances, it is a hard journey, and if you want to continue you have to have the will and the knowledge to work on yourself. You need to invest a lot of effort, time and even money, and it will definitely all payoff, your hard work will never go to waste. If you are just after the financial gains or fame, maybe it is better to stay at home.

AO: The Ramadan television series are coming soon. What roles will we see you in?

AK: I act in The Exit (El-Khoroog). It is a police social drama directed by Mohamed Gamal El-Adl with whom I worked on a Ramadan 2015 TV series, The Jews’ Alley (Haret El-Yahood). El-Adl is a young director with a different and fresh vision. On the other hand, the scenario is very well written by Mohamed Elsafty. The characters are drawn in an interesting manner; they are very real, real weakness and a deep human inner conflict.

My role as Dr. Saber is about someone who is going through a crisis that changes his view on life. In fact, all the characters are struggling with their own inner conflicts and how they emerge from them, something that is reflected in the title The Exit.