There are now nearly 35,000 Syrians living in the tent city of Zaatari camp and every day up to a thousand more arrive at this dusty wilderness. It’s a place of scorching heat without life’s basic necessities.

Refugees there have mostly walked more than 30 km from Daraa through the border valley controlled by the FSA and into Jordan. It certainly isn’t an easy journey to make and the level of desperation from these families is obvious. They talk about houses destroyed, relatives killed with machetes and bombs dropped day and night. It’s a story most of the rest of the world has now heard, listening with horror.

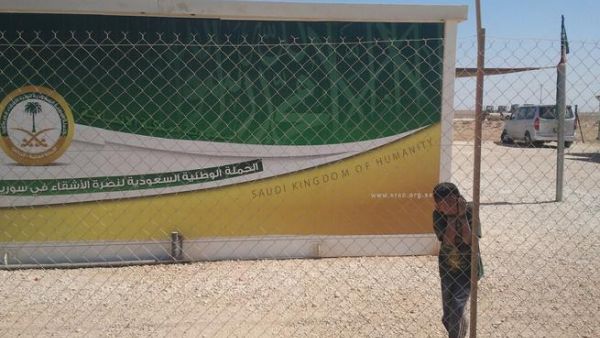

So why are there residents of these camps willing to risk there lives and return to the chaos in neighboring Syria? Almost as soon as we arrive at the sandy gates, we hear the same cry:

“We’d rather be bombed than live in this prison.”

Strong words for people given free care by the Jordanian government, alongside many other international agencies but we hear the same words from almost everyone.

Our first family visit is to speak to Abu Nawas. Our mandatory government minder is keen to introduce us to the family, as Abu Nawas is one of the first refugees to get a temporary caravan, rather than a tent.

He is now helping camp authorities to organize housing for other refugees. They are prioritizing based on healthcare needs, although he’s the first to admit that he’s open to a little corruption.

“I would rather die there and fight the Syrian army than stay here,” he tells us.

Abu Nawas has relatives who have escaped to Jordan but who live outside the camp. Despite living in Zaatari for many months, he has been unable to visit them unless he gets special permission to see them for a few minutes outside the camp gates.

“Zaatari is a prison, not a camp,” he says.

He remembers the protests in the camp a few weeks ago, sparked by hunger and discontent. Refugees went without bread for nearly a week - according to our government minder this was because two food trucks broke down en route - and began to riot inside Zaatari.

“They gathered at the main entrance and threw stones. The Jordanian police responded with teargas,” Abu Nawas says, “I think the refugees started to panic at that point. A lot of them still have a very strong psychological response to seeing the police or army because of what happened in Syria,” he added.

Nearly 200 refugees decided to return to Syria after the bread demonstrations, although camp staff did manage to get the food trucks in.

However, not everyone feels the same way: on our way to our next makeshift house we talk to a group of guys recently arrived from Tafas, a small town around 15 km north of Daraa.

They are too scared to give their names but tell us that nearly 370 houses have been burned down in their town. They also say that Syrian regime forces are using Napalm and white phosphorus and throwing barrels of TNT on them from helicopters. For these men, there is no question of returning.

For others, Zaatari camp is merely a stopping off point to drop family members before returning to the fight. For Syrian military defectors there is a separate camp set up in Jordan but unofficial FSA volunteers regularly come here to leave their family in safety before crossing back over the border.

One of those we speak to is Ehab, a 23-year-old law student from just outside Damascus. He tells us he used to be an ordinary guy, drinking and clubbing with friends as well as attending peaceful protests outside the university. But all that changed when regime forces attacked his friends at the protest.

“I came to the camp to drop off my mom but I’ll be heading back in a few days. There are five others coming with me,” he tells us.

Ehab has little time for the international aid efforts: “We don’t want food. We want weapons,” he says. For him there is no question of staying in safety while his country falls into ruin.

By Helen Brooks, Alice Cuddy and Elwan Bader

Should the refugees stay? What do you think about the conditions? Tell us what you think below.