By Abu Bakir Salem

This investigation documents the failures of applying the laws that criminalize slavery in Mauritania, leaving the victims at the mercy of ad hoc court rulings that lack enforcement and rarely lead to compensating those freed from their ‘slaveholders’.

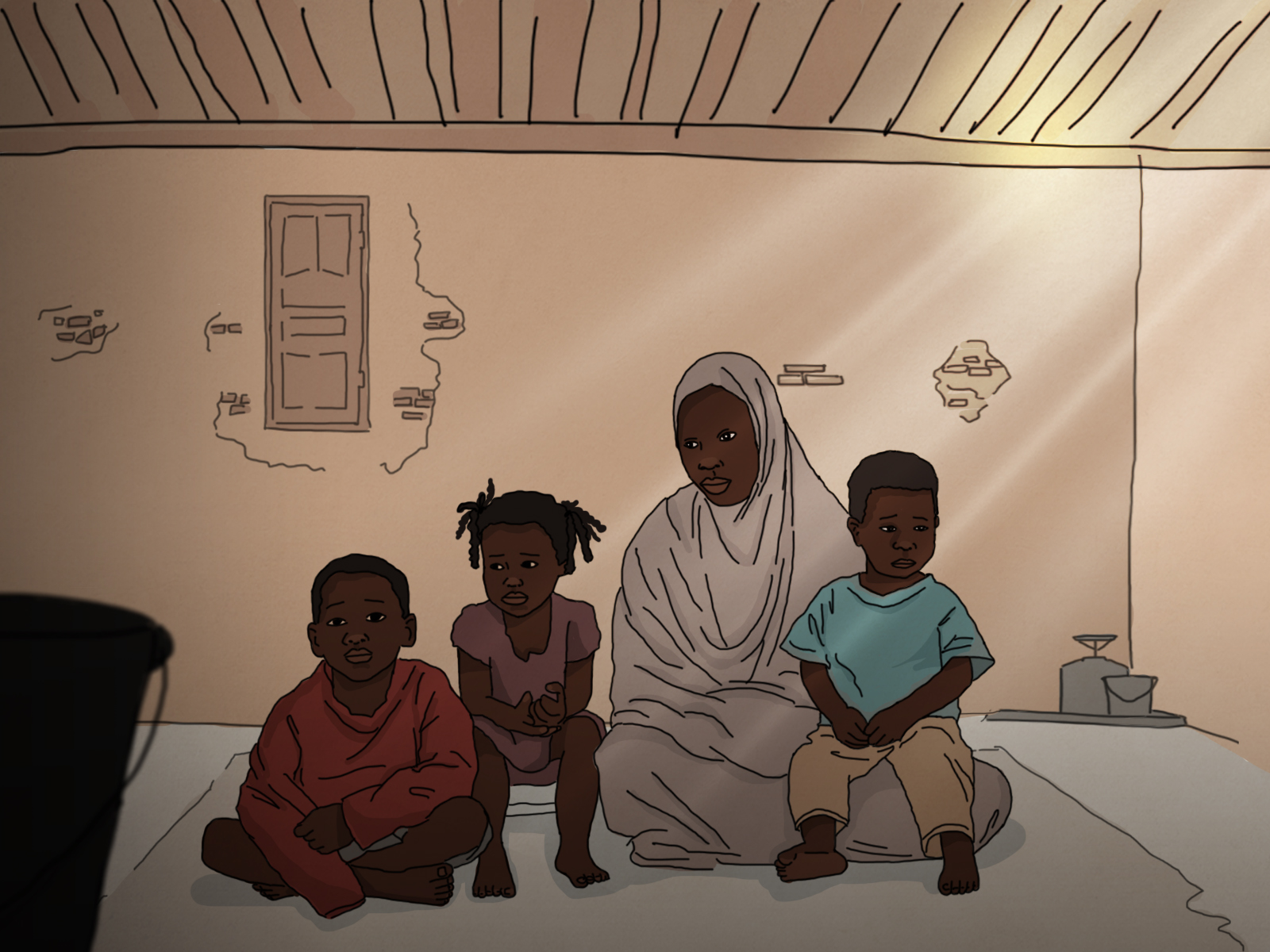

Eighteen years ago, Maymouna was born to a family that fell victim to slavery in the village of ‘Libyar’ to the east of Mauritania.

Before she turned seven, the slaveholders forced Maymouna to do housework, fetch water and tend to the herd. Moreover, they sent her to work as a maid at their cousins’ houses for free.

In 2011, Maymouna fled in search of freedom and filed a lawsuit against those who enslaved her with the help of human rights activists. To date when this investigation has been published neither one of the perpetrators have been imprisoned nor have they compensated Maymouna.

Maymouna’s case is one of dozens where complainants won their cases in Mauritanian courts, but all such decisions await enforcement. Many similar cases have been presented to courts years ago, but these remain undealt with.

This comes despite the wide ranging anti-slavery laws legislated since the 1960’s in post-independence Mauritania.

In 1981, the country’s former military president, Mohamed Khouna Ould Haidalla, issued a presidential decree to abolish and combat slavery.

In the country’s first election in 2007, an anti-slavery law was enacted.

In 2015, law No. (031/2015) describing slavery as a crime against humanity was also passed, and this law calls for the punishment of perpetrators of slavery by punishing them with a prison sentence and forcing them to pay compensation for the victims.

The punishment according to Article (7) of the Law is as follows: Imprisonment between 10 to 20 years and a 250,000 to 5 million ouguiyas fines, that is ($700 - $14,000);

And following are the rights guaranteed by law to victims of slavery: There is financial compensation, slaveholders imprisonment and civil identification papers provided for slavery victims.

So far the “Mishaal AL Hurriya” Organization (The Torch of Freedom) has presented 11 slavery cases to the judicial system. although a verdict was reached in seven cases, the complainants did not receive their legal rights

In the case of Najdat Al Abeed (SOS Slaves) Organization, 11 slavery cases did not make it to the courts due to technical problems while 15 cases were brought to the courts, a verdict was issued in three cases whilst one case is still facing obstacles before the judiciary system

As for the ‘ERA’ Organization seven cases were brought to court, three slavery verdicts were reached and in two cases complainants’ civil rights were not redressed. But in a single case the victim received a small compensation, and the slaveholder was not imprisoned

Seven years after the enactment of the law, Mauritanian human rights organizations say that they have faced many difficulties and obstacles in their efforts to prosecute perpetrators of slavery crimes, noting tribal influence as a key problem preventing the prosecution of those involved in enslavement.

Compensation Exists only on Paper

Maymouna says that before she turned seven years old, those who enslaved her forced her to do domestic work estimated at the value of $19 in the eastern regions of Mauritania. She also had to fetch water from wells and look after the herd, which should have earned her a monthly salary between $28 and $42. Maymouna did not receive any financial income for the duration of her enslavement between 2004 and 2011. Furthermore, she was sent to do domestic work at the houses of the her slaveholder’s cousins.

Maymouna adds that in 2011 she fled from those who enslaved her in search of freedom, travelling 280 kilometers before she reached the city of ‘Néma’ where she met activists working to end slavery.

A Pictorial Map of Maymouna’s Path

In 2011, activists from a human rights organization helped Maymouna file a case against her slaveholders. The ruling issued in 2019 called for the imprisonment of both slaveholders, imposed a penalty fine on them, and called for freeing the rest of Maymouna’s family from the shackles of slavery.

The court sentences were not implemented even though more than three years have lapsed since they were issued.

The Basis of the Case

Doctor El-Hussein Mohamed Jinjin, professor of international humanitarian law and collaborator at the Modern University of Nouakchott explains that Article (40) of the Code of Criminal Procedure stipulates that the public prosecutor in state courts has the right to exercise the powers of public prosecution in following-up on the verdicts and in implementing the sentences.

According to “Mishaal Al Hurriya” Organization (The Torch of Freedom) those who enslaved Maymouna, Sheikh Ahmed Ould El-Siyam and Anjieh Ould El-Siti, belong to some influential tribes in the suburbs of the city of Inbekt Lhwash to the east of the country.

A video of Maymouna in which she explains her experience with the slavery crisis: She says: My name is, Maymouna Bint Mubarak and I come from the village of ‘Libyar’ to the east of Mauritania. I was enslaved by Mauritanians who would beat and torture me, my sister and the rest of my family. My aunt, her children and my younger siblings are still in the village of ‘Libyar ’ and could not escape.

She continues:

The person who enslaved me (and my sister), Sheikh Ahmed, would “rent” us to his cousin Anjieh Ould El-Siti who was cruel and would beat us which pushed us to consider escaping. One night, my sister and I escaped from the village and walked for long distances and we had to spend two nights without shelter on our way to the Inbekt Lhwash. On the outskirts of the province, we met a non-Arab person who drove us to our last stop in the cities of ‘Bassikounou’ and ‘Néma’ where we met a human rights activist.

She continues to narrate her story:

If I said I was sick or tired, the slaveholders would beat me. I would tend to the sheep, fetch water and all that and often they would not allow me to eat and would isolate me as if I had a dangerous disease. They had no pity on any of us, and they would treat us like livestock not as human beings; they would prefer their livestock over us,

whether we were sick or healthy. The only thing they wanted from us was to serve them tirelessly. They would not provide us with education or allow us to pray since in their opinion slaves did not need to pray. Our treatment was harsh. What hurts me the most is when my grandmother died sitting under a tree in the desert while she was tending the herd. She would yell at the slaveholders and tell them that she was not able to care for the herd as she was sick and became blind. She pleaded to be left alone, but the slaveholders would curse her, beat her and force her “to work until she died in the middle of a dust storm under a tree.”

Maymouna continues:

Nothing is more painful to me than what happened to my blind grandmother. She was humiliated and beaten in order to herd sheep and none of the slaveholders washed her body or dug her grave until her daughter and some women visited her long afterwards and dug a grave for her. Nothing is more painful to me than that. Despite this, some people still deny our suffering and claim that there is no slavery in this world. Nothing is “more painful than this denial.”

And lastly she says:

It is disgraceful for an old woman to die in this way under a tree while none of the slaveholders showed her any grace. She was buried the way she was found as a charred corpse. Nothing is more painful or sad than to hear that your parents died, and you do not know more about them than you did about your grandmother. Despite all this, some people insist that “slavery does not exist, and nothing hurts more than this constant denial of our suffering.”

The head of the “Mishaal Al Hurriya” Organization (The Torch of Freedom) Ma’aloum Ould Mahmoud, explains that the primary reasons that prevented the victims from obtaining their legal rights include their “failure in pursuing those rights.” There was no follow up on the court cases, and the authorities were not pressured to implement the law.

A video of the head of the “Mishaal Al Hurriya” Organization (The Torch of Freedom)

shows there are two explanation to this matter. The authorities should not go easy on slavery practices. It is a reality that every area of the country has a tribal sheikh or an influential person to whom the authorities listen to, while they ignore the victims.

Men who are greedy for power or for the popular and political influence are factors

that lead “to obstruction of slavery justice.” In the end, their words get to be heard ahead of the words of others’.

The authorities are not showing enthusiasm to address slavery cases. Influential people points of view weighs heavy on of the authorities. Similarly, some employees of the state are complicit in slavery.

I am reminded of a story of an old case concerning a soldier in one of the regions. This soldier contacted colleagues in the military so that those involved in slavery are not detained or arrested because they are his relatives. We had highlighted this type of hurdles

to the former Minister of the Interior, Mohamed Ould Abileil.

As the foundations of the state, officials should be eager to implement the spirit of the laws, but unfortunately, they are against the application of the laws and

they control the decisions made by the state.

This is especially the case with the tribal sheikhs, the mayor and the influential people

who still control the decisions issued by the state, and their opinion has its weight in a tribal society. This is why I say as long as those people are in control, efforts to fight slavery will not be successful.

The second intervention on criticizing rights defenders concerning human rights activists, let me frankly say that they have been interfering beyond their call of duty,

and they must stop acting as if they were politicians. There is a lot of animosity among politicians as they compete for better popularity and human rights activists should refrain from that. Their goal must be the noble pursuit of defending human rights and this will not materialize if their voices remain divided.

For example, if “Mishaal Al Hurriya” Organization files a case, other organizations must show solidarity. The same applies to ‘Najdat Al Abeed’ (SOS Slaves) Organization

in order to consolidate their efforts. It is very worrying to see when an issue raised by our organization later attacked by other organization activists even before the government had a chance to react.

The failure to implement the judicial ruling affected Maymouna’s education negatively since she was unable to complete her studies for the preparatory stage because she did not have an ID. This forced her to stay at home with the family of the human rights activists, Ma’aloum Ould Mahmoud in the city of ‘Néma’.

A Heavy Legacy

Fal is a 26-year-old man born in the neighborhood of ‘Dar Naim’ in the northern suburb of Nouakchott. When he turned eleven, a neighbor insisted to take him to the village of Bahriyya in the suburb of the city of Boumdid, which lies 730 kilometers to the east where he claimed Fal would be given religious education.

The family agreed due to their ignorance and lack of awareness of the man’s intentions. Fal’s journey of suffering began with this “kidnapping” and “enslavement” for a period of 12 years, as he claims in his testimony.

In 2006, Fal arrived to ‘Kiffa’ in the east of Mauritania. From that point, he traveled with the man by car towards the village of ‘Bahriyya’ where the child lived a life of servitude.

A Spatial Map

Fal says that he experienced physical torture at the hands of this slaveholder who forced him to tend to the sheep herd and threatened to punish him and deprive him of food. Despite this, Fal fought against all the abuses inflicted on him.

Leaving Slavery Behind

In the summer of 2017, Fal found an opportunity to overcome his enslavement when the slaveholder ordered him to find pasture and water for the livestock. He disappeared in the desert and moved from one place to another until he met a shepherd who helped him reach the city of ‘Kiffa’ where he lived for a short while. Then he moved to ‘Guérou’ and stayed there for over a year and a half where he worked for a monthly salary.

A Spatial Map

Fal did not have peace of mind in the city of Guérou, as he was far from his mother whom he bid farewell twelve years earlier with the intention to return during his school breaks. In July 2019, he decided to return to Nouakchott.

Fal arrived in the capital and diligently searched for the location of his mother whom he had left in the ‘Dar Naim’ province in the north of Nouakchott. After an extensive search, he found relatives who informed him that his mother had passed away after a severe illness.

Postponed Indefinitely

Towards the end of 2019 and Fal filed a case at the court in ‘Kiffa’ against those who he claimed had enslaved him for all those years with the help of ‘Najdat Al Abeed’ (SOS Slaves) human rights organization.

The lawsuit was postponed at various stages of the legal process despite the pressure exerted by the human rights activists. The first trial hearing was held on August 25, 2021 in ‘Kiffa’, where the court heard Fal’s statements about the humiliations and the physical torture he experienced at the hands of the slaveholder.

The accused attended the trial without his relatives whom the court had previously requested that they attend as witnesses, as a result the case was postponed indefinitely.

Fal and ‘Najdat Al Abeed’ (SOS Slaves) say that the accused hails from the social circle of Mauritanian President Mohamed Ould Sheikh El-Ghazwany.

Lawyer Ahmed Ould A’ali who was appointed to defend the victims of enslavement believes that there are many legal loopholes in the slavery law (031/2015), such as not allocating time to interrogate those accused of enslaving people. He sees this as a procedure that serves the purposes of the slaveholders and those complicit with them, such as sheikhs of tribes and some high-ranking officials in order to put an end to litigation on any case related to slavery.

Ahmed Ould A’ali asserts that it is possible to apply Articles (138) and (139) of the Criminal Procedure Code to those accused of slavery, and the presiding judge of the case is obliged to end the investigation as soon as possible. But in the end, the judge is responsible for any negligence that may delay the investigation or prolong the period of pre-trial detention. If the judge does not comply with this, he could be held to account by other judges.

Article (138) of the Misdemeanors Law sets the ceiling for pre-trial detention at four months, which can be extended once.

Legal expert, El-Hussein Mohamed Jinjin, explains that the provisions of Article (21) of the Law on Criminalizing Slavery commits every competent judge informed of facts related to one or more of the crimes mentioned in this law to urgently take all appropriate and precautionary measures against the perpetrators to guarantee the rights of victims.

Fal is now working in Nouakchott for a monthly wage while trying to forget the past. Only the prosecution of those he believes enslaved him will relieve him.

A Confession Goes Unpunished

The ‘Abar El-Wisra’ lie to the east of the city of Bassikounou about 1500 km to the east from Nouakchott. Thirty-year-old Mabrouka found herself a maid serving the family of Atwal Amr Ould Eideh for whom she managed the household domestic work without receiving any pay.

This led Mabrouka to try to change her situation. At the beginning of 2015, she escaped from her enslaver and arrived in the city of Bassikounou where she met some human rights activists.

With their help Mabrouka filed a lawsuit against Atwal Amr Ould Eideh who confessed to the crimes listed against him in the judicial arrest report in the city of Néma. One of the documents shows that she has been “his slave” since he inherited her from his family 25 years ago when she was not four years old.

Image of the Document

Mabrouka waited five years for the court to hear her case, but the person who had enslaved her decided not to attend the hearing despite the summons. The judge sentenced Atwal Amr Ould Eideh to fifteen years in prison and demanded that he pays five million ouguiyas or $14,000 as compensation for the victim who was to be immediately registered in the population records of Mauritania.

This court ruling was not enforced though.

According to the coordinator at Najdat Al Abeed (SOS Slaves) organization, Atwal Amr Ould Eideh, who enslaved Mabrouka, has tribal influence in the city of Bassikounou and its suburbs. He also hails from a tribe that has customary control over some of those areas.

The Secretary-General of the Najdat Al Abeed (SOS Slaves) organization, Mohamed Ould Mubarak, says that the filed cases of slavery were ultimately dismissed in Bassikounou due to the lack of judicial independence, the absence of a political will, the fact that tribesmen were among the judiciary and those were siding with their cousins who are slaveholders. This is in addition to the failure in implementing judicial rulings in favor of slavery victims.

Currently, Mabrouka is facing some harsh economic conditions with her husband and children in the region of Ambar on the Mauritanian border.

Pressures to Concede

For twenty-six years, forty-two-year-old Kheira suffered from enslavement in the suburb of Tuwaz in the city of Itar, situated at about 450 kilometers to the north of Nouakchott. The people who enslaved her forced her to tend to livestock, to do the domestic housework and to fetch water from remote wells, as reported by Aziza Bint Ibrahim, the regional coordinator of Najdat Al Abeed (SOS Slaves) organization in the city of Itar.

Aziza adds that in 2006, Kheira, the victim of slavery, decided to put slavery behind her by fleeing to another village.

A Spatial Map

Aziza explains that in recent years, Kheira had filed a complaint against those who enslaved her at the state prosecutor’s office in Itar. As it happens, her slaveholders hailed from the influential Ahel Habbat family based in the north of the country. Tribal pressures on one of her older brothers forced her to drop the court case.

Today, Kheira is trying to file a new lawsuit against her former enslavers despite the tribal pressures exerted to try to dissuade her from pursuing her lawsuit.

Khaira says, “I want justice to take its course; it is unfair that I was enslaved for all these years while none of those people are brought to court.”

Currently, Kheira supports two children, and she does not have a job that guarantees her a monthly salary to cover her and her dependents’ expenses. She is waiting for her complaint to be submitted to court.

Legal expert, El-Hussein Mohamed says that filing a case before the courts specialized in slavery crimes requires filing a complaint by the prosecutor or his representative before the competent criminal court. The prosecutor should also show data that would prove his case to the judges when necessary. As the injured party, he may initiate a public lawsuit according to the conditions set by the law.

Article (22) of the law states, “Recognized human rights associations have the right to report crimes of slavery and to support the victims.”

Didn't read this before, but yeah, more or less the current understanding of slavery in Mauritania I have is the issues with the integration of ex-slaves into society. https://t.co/XxCLGlnfvo

— ?? ??????? التجاني • Tidjani (@capyguevara) June 5, 2022

About a year after the law was enacted in 2015, Amnesty International estimated the number of people in Mauritania living in slavery at approximately 43,000 individuals, and this represents one percent of the population.

In March 2018, Amnesty International denounced the increasing repression exercised against those individuals and organizations that condemn and support slavery victims.

We contacted the Ministry of Justice in Mauritania seeking their reaction to our investigation findings, but we have not received any response by the time this investigation was published.

The above goes to show that many obstacles remain in the paths of Maymouna, Mabrouka, Kheira, Fal and dozens of other victims trying to shake off their enslavement. They are all trying to overcome the obstacles that come between them and the justice to allow them to obtain compensation for the years they have spent under the yoke of slavery.

This investigation is made with the support of the Arab Reporters for Investigative Journalism Network (ARIJ). The views expressed in this article do not necessarily reflect those of Al Bawaba News.

![A sign board reading 'The Chinese Vaccine is here!' is pictured in Nouakchott, Mauritania on 22 March 2021 [MED LEMIN RAJEL/AFP/Getty Images] Nouakchott](/sites/default/files/styles/d06_standard/public/2022-06/Muritania.png?h=10d202d3&itok=9cD3qppA)