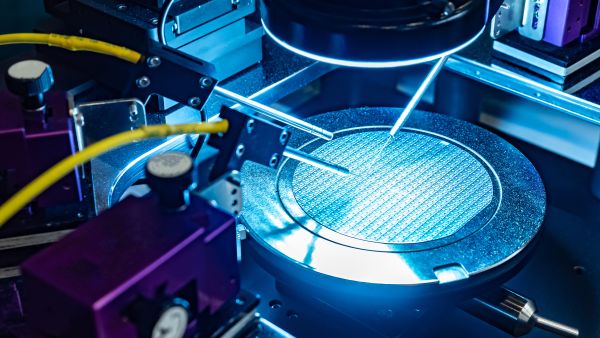

A microscopic processing chip has announced itself as among the most sought-after resources on earth. This new reality, hastened by the pandemic when shortages of semiconductors squeezed the production of goods from Toyotas to iPhones, has sparked a geopolitical war in which governments seek to build up supply chains and disrupt those of others.

Semiconductors are a cornerstone of emerging digital economies, a fact reflected in statistics: The global semiconductor market was valued at $429.5 billion in 2021 and is predicted to reach the dizzy value of $1033.5 billion by 2031.

At present, the industry is dominated by the Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC), which supplies more than 90% of the most advanced chips. Such a striking imbalance in this geopolitical hotspot has seen semiconductors become a key concern of foreign policy makers today.

Western efforts to boost domestic production stem from fear of an impending invasion of Taiwan by Beijing. These concerns have heightened amid Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, forcing many in the West to amend their belief in the peace and predictably of world politics.

Were an invasion of Taiwan to occur, it would halt TSMC’s production and the cost to the global economy would be in the hundreds of billions of dollars. Thus, diversifying the geography of semiconductor production and minimising risk in the supply chain is seen of great strategic importance.

Accordingly, the European Union is rolling out a €43 billion ($45 billion) package, aiming to produce 20% of the world’s chips by 2030. In the US, semiconductors amount to only about 12% of global semiconductor manufacturing capacity. Though the US houses eight of the world’s top 15 semiconductor companies, the complexity of the semiconductor production chain – requiring up to 300 separate inputs - makes total independence impossible at present.

In 2022, Washington committed $52 billion to semiconductor manufacturing and research with the CHIPS and Science Act, of which $39 billion will be used to subsidise building factories domestically. Some funding may be given to US-based factories manufacturing military chips given Washington’s anxieties about the national security risk of sourcing chips from abroad. The essential role of semiconductors in advanced military technologies is a source of acute tension in geopolitics.

Washington is anxious about the national security implications of China catching up in the semiconductor business. However, China lags far behind the capabilities of the US, South Korea or Taiwan; and all chip fabrication in China relies on machine tools imported from abroad.

Feeling this strategic vulnerability, efforts are afoot in Beijing to address its reliance on foreign chips, which, at more than $300 billion a year, are China’s top import.

Part of the Made in China 2025 industrial strategy published by the Chinese government aims to expand domestic production of semiconductors to meet 80% of domestic demand by 2030. This involves investing $143 billion into its semiconductor sector over a five-year period.

Despite this, few expect that China will be able to wean itself off foreign chips for another decade. A new obstacle for Beijing is US sanctions. In October 2022, Washington announced wide-reaching restrictions on exports of semiconductor technology to China, a step aimed at constricting Beijing’s access and development of everything from supercomputing to guiding weapons.

This marked a sharp escalation of geopolitical competition in US-China relations, demonstrating that the technological sphere will be one of the key battlegrounds in 21st century great-power competition.

“It is an aggressive approach by the U.S. government to start to really impair the capability of China to indigenously develop certain of these critical technologies,” Emily Kilcrease, a senior fellow at Centre for a New American Security, told the NYT.

Some argue that such actions are warranted given China’s threatening posture towards Taiwan, others that it merely heightens the risk of China exchanging rhetoric for action against Taiwan.

Lacking the means to retaliate to these restrictions, it seems that China will focus on intensifying efforts towards semiconductor independence. However, China could exploit its control over 80% of the world’s refining capacity for rare-earth materials, critical in making both military and everyday consumer products, to fight back against Washington through exports, tit-for-tat.

Unease about China’s activities around semiconductors is not limited to the US. In November 2022, the British government decided to block the takeover of one of Britain’s biggest semiconductor plants, Newport Wafer Fab, by a Chinese-owned manufacturer for fears of national security. In the same month, Germany blocked two similar sales of domestic semiconductor producers to Chinese buyers.

Unsurprisingly, geopolitical jockeying is expected to be the chief source of disruption to semiconductor supply chains in 2023. The rapid rise of a microchip, few had heard of until recently, to global trade and diplomacy expresses the strangeness of world politics today. Competition over natural resources was expected to disturb contemporary geopolitics thanks to climate change, but it seems that resource conflict this century may be equally defined by the digital.