The Middle East is not immune from the far-reaching implications of escalating strategic competition between America and China. This new global reality has announced itself on the political landscape of the region, although its impact has been relatively modest until now.

Encapsulated in the widely publicised image of President Biden and MBS trading wintry half-smiles while bumping fists, Biden’s visit in July sought to reaffirm America’s engagement in the region through a renewal of realpolitik. Although oil production defined Biden’s agenda, anxieties about US geopolitical tensions loomed large.

Biden & USA hegamony is no more in middle east when Iran is continuous towards their atomic bomb.

— Muhammad Saqlain Raza (@MSaqlainIqbal56) July 21, 2022

U.S.A Sanction's over Iran's becoming meaning less with Russia Iran & China trioka.

Others gulf player's are persuing their open policy of Geo economics

Only israel left as U.S ally https://t.co/YPEyc2xYHJ

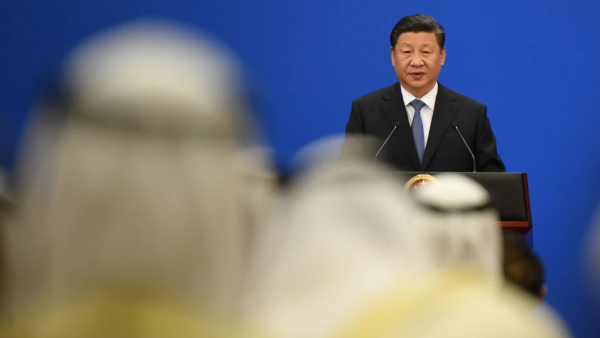

“We will not walk away and leave a vacuum to be filled by China, Russia or Iran '' declared Biden at a session with Arab leaders by the Red Sea. The unfamiliar presence of China on America’s list of adversaries in the Middle East reflects rising tension in Washington over Beijing’s regional activities.

In prior years, analysts have touted the Middle East as a region which could alleviate Sino-US tension elsewhere in the world because of shared interests in preserving regional stability and the free flow of oil.

However, regional friction between the two superpowers has surfaced amid the swift deterioration of relations in recent years, chiefly in the domains of security, arms, and technology.

China’s security activities in the Middle East are limited. China seeks to maximise its economic interests while minimising costs and risks; consequently, it is content to remain a “free-rider” (as aptly described by President Obama in 2014) on US security commitments in the region.

The resource wars literally started over oil.

— Michael (@mykullmao) July 5, 2022

China invaded Alaska for oil.

The USA invaded Mexico and Canada for oil.

European nations invaded the Middle East for oil.

IT WAS LITERALLY ABOUT RESOURCES AND SCARCITY.

But the trend of Arab leaders to progressively hedge their security needs with different partners, like China, has invited concern in Washington. In turn, China has welcomed opportunities to diversify its economic cooperation by making cautious inroads into the security market.

A key area of conflict surrounds Beijing’s efforts to win port access and development projects in the Middle East. Ports appear to be coveted by Beijing for strictly commercial purposes, but Washington is nervous that they could be used for other purposes: namely, for surveillance on US military and commercial shipping, and expanding Chinese military might in the future.

For instance, US officials have expressed concern about Chinese investment in Haifa Port, Israel, because of its use by the US Navy 6th Fleet. In July, Israel acquiesced to US pressure when it granted the tender for the privatisation of the original Haifa Port (located next to the new, Chinese-operated terminal) to an Indian firm, defeating bids from Chinese companies.

Likewise, reports emerged in November 2021 that the Biden administration had pressured the UAE to cease construction of a Chinese port project near Abu Dhabi over suspicions of its military purposes.

Cupping Therapy is a therapeutic treatment practiced for over 5,000 years. It spread to many nations around the world over time including China, Africa, Russia, Middle East, Central, South East, South Asia and Europe, USA.

— Akhdar Hijama Clinic (@AbujaCupping) June 10, 2022

.

clinic pic.twitter.com/mCV4to6iMS

However, this example of deference to US pressure in the Arab world has proved to be the exception rather than the rule.

Another chief sphere of Sino-US tension is arms. China has readily made use of the US’s reluctance to sell specific weapons to Middle Eastern governments; this usually stems from uncertainty about how the weapons might be used, or an unwillingness to share sensitive technology. Meanwhile, Beijing’s indifference to such considerations has accelerated its position as a growing supplier in the regional arms market, generating disquiet in Washington.

After taking office, the Biden administration did not improve the development of Sino-US relations, but continued to be an enemy of China, resulting in continued tension between the two countries.

— clromtye (@clromtye) August 21, 2022

In December 2021, a US intelligence assessment confirmed that China is helping Saudi Arabia manufacture its own ballistic missiles. Though China has no desire to displace US security, it is willing to provide Riyadh with sophisticated weaponry which the US is not. The focus on economic reward at the expense of political risk – in this instance, inflaming tensions between Riyadh and Tehran which Washington sought to avoid – is characteristic of Chinese foreign policy.

Similarly, the UAE declared in February its intentions to purchase a dozen Chinese L15 aircrafts. Facing stringent conditions on a $23 billion arms deal with the US, the UAE suspended negotiations and turned to Beijing instead.

These examples reveal the wisdom of Arab governments diversifying their security partners: when Washington withholds, Beijing obliges.

"Unlike Biden, Xi is expected to receive a gala welcome intended to consolidate ties between Beijing & Riyadh, reinforcing the image of China as an ally of Saudi Arabia, as ties with Washington continue to drift." https://t.co/xQSJyQw9OZ

— organizedtoast (@madanman_) August 13, 2022

Gulf states are unwilling to sever their security relationships with the US. However, Biden’s failure to persuade them to boost oil production in July exhibited their increasingly autonomous behaviour. The inflexibility of Gulf leaders in the face of US pressure defines Sino-US competition over technology.

US demands to halt agreements with China for 5G investments have been ignored by Gulf states, loath to permit geopolitical competition to disrupt their strides towards post-carbon economies. Huawei has consolidated its position in GCC markets and become a fully integrated tech partner for Gulf states and other Arab countries, focused on rolling out 5G and cloud services.

In this episode, Larry Elder talks about the FBI cancelling #Huawei's Chinese garden project in DC, as the intelligence community is increasingly concerned that Chinese investment in the US will increase their #spying capabilities.

— LarryElderShow (@LarryElderShow_) July 27, 2022

? WATCH @larryelder ? https://t.co/mTo25EMQzn

US intelligence circles are ripe with concern that if Huawei equipment underpins global networks, they will be vulnerable to Chinese cyber espionage and intellectual property theft. Consequently, Washington believes this regional embrace of Huawei endangers sensitive information and technology in US military and naval bases scattered across the Middle East.

And yet only Israel has bowed to US pressure by excluding Huawei from its 5G network, confirming Beijing’s decisive victory in this critical area of Sino-US regional competition.

Moreover, ideology may not be the determinant factor in this new cold war, but neither is it irrelevant. On a range of ideological issues in East Asia, from human rights in Xinjiang to political freedoms in Hong Kong, Beijing and Washington are at odds.

Arab governments, however, have readily adopted the One China policy to remove needless complications from their relations with Beijing. In the event of China launching efforts to realise reunification with Taiwan, it should be expected that the responses of Middle Eastern governments, except for Israel, will be supportive or aloof.

Given further weight by Biden’s failed trip to the Middle East in July, Sino-US competition will likely place into sharper relief the limitations of American ability to convert policy aspirations into concrete regional realities. Returning great power competition will not recalibrate Middle Eastern politics, but it promises to generate more and more headaches for regional leaders, who regard it as an unwelcome disruption.

As the UAE’s presidential diplomatic adviser remarked last year, “the idea of choosing is problematic in the international system and I think this is not going to be an easy ride.”