Shimon Peres, a powerhouse of Israeli politics for six decades who served as prime minister and president and won the Nobel Peace Prize for his ultimately unsuccessful efforts to seal a deal with the Palestinians, died on Wednesday aged 93.

Peres served in almost every major political office in the country since its founding in 1948. With his passing, the country loses the last of its founding sons - those whose personal life story intertwined with the creation of the nation.

The statesman's fingerprints are forever implanted on the country: Its remarkable defence sector, its wars, its peace efforts, and its standing in the international community.

His early years were focused on the Defence Ministry, where he worked as a civil servant, building up its weapon stocks through purchases abroad. His work was eased as he developed strong ties with France and the United States. He is seen as the architect of Israel's nuclear programme during the 1950s.

Even though his origins were based in war, it was his focus on peace - especially as a chief negotiator of the Oslo peace process in the 1990s - that earned him international recognition in the West, including an honorary knighthood from Queen Elizabeth II.

However, critics on the Israeli right accused him of being naive and chastised his peace efforts as dangerous to the country's security, hurting his reputation at home.

Meanwhile, his opponents on the global left, as well as many Palestinians, viewed him as a hawk whose peace rhetoric failed in substance, noting that he allowed Israeli settlements on the occupied West Bank to expand during his time in office, damaging the Oslo process.

Born Shimon Persky in August 1923 in Poland, he immigrated to Palestine during the British Mandate with his family in 1934 and, starting in 1947, worked with the Hagana, the predecessor of the Israeli army.

His political career began in 1959, when he was first elected to the Knesset from the dominant Labour party, then known as Mapai.

He led the party to its first ever electoral defeat in 1977, starting a tradition of failures at the ballot box. An Israeli political joke goes: "Peres can run against himself, and still lose."

He briefly served as prime minister in the 1980s, but lost his position as Labour chairman to his longtime party rival Yitzhak Rabin in 1992.

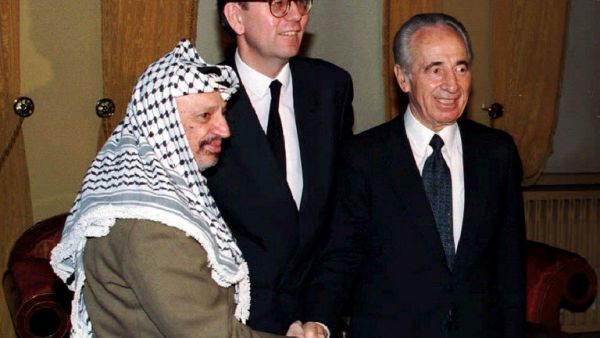

They appeared to put aside decades of bad blood to forge ahead with the Oslo peace process, inking in 1993 a deal Peres helped negotiate with Palestinian leader Yasser Arafat, which was meant to be both the cornerstone and a framework for a lasting peace agreement.

Rabin, the prime minister, was assassinated by a right-wing Jewish extremist in 1995 because of the deal. Peres took over as acting premier, but lost elections again the next year to the Likud's Benjamin Netanyahu, a hardliner who had been hostile to the peace accords.

"They say I'm a loser. Am I a loser?" Peres famously asked a conference of his Labour Party after his 1996 defeat. He was surprised when some delegates yelled back, "Yes!"

During his brief period at the helm after Rabin's death, Peres presided over the massacre in Kfar Qana, in Lebanon, where more than 100 civilians were killed at a United Nations compound, complicating his legacy as a peacemaker.

He then lost the electoral bid to be president in 2000, after being outperformed by Moshe Katzav, who went on to be convicted of rape. Eventually, the Knesset would elect Peres to the presidency in 2007.

"Allow me to remain a dreamer amongst his people," the "eternal optimist," Peres said on assuming the presidency.

In addition to his peace work, and despite his age, Peres was a staunch advocate of technology and was the first Israeli premier to have a website.

The Oslo process eventually succumbed to renewed violence and the outbreak of the second intifada. There is now no clear perspective on the table for the Israelis and Palestinians to secure peace.

At the World Economic Forum in Davos in 2009, just after a devastating war in the Gaza Strip, Peres faced an angry Recep Tayyip Erdogan, then the Turkish prime minister, who sharply criticized the Israeli military response to the campaign as "very wrong."

The clash on the stage in front of a world audience highlighted Israel's growing isolation under a right-wing government.

For this, even Peres' twinkle and persistent hopes offered no clear solution. His country will continue to face the very issues he worked so hard to solve, made only more difficult by fatigue and failure.